Tatiana Otzoup Guliaeff and her parents survived the Holocaust and World War II through the efforts of a close friend, her godfather Albert Goering, who provided the familie with false papers. She was only six years old when she saw him for the last time in Vienna.

Later she wanted to relate her experiences during WWII but was told not to try and imitate her uncles, who were writers and poets, one of them founding The Poets Guild in Paris.

But Tatiana wrote Answer To My Son when he asked her what her feelings were and what she did between the ages of four and eight, 1939 to 1943. Her memoirs are compiled of vignettes and stories that are based on facts and embellished by her own feelings and recollections, thus working themselves into a wonderful Patchwork Quilt Of Memories.

"When my son, recently, asked what I thought of, what my feelings were and what I did between the ages of four and eight, it was impossible to answer that question and be understood. Our children cannot grasp the concept of what it was like to, not only grow up during the war, but to live through the nightly and then daily bombings, of first having a limited food allowance and then, bordering on starvation, taking from nature what was available. The wild onions and garlic probably saved us from scurvy. The flowers of the wild clover provided us with the necessary sugar, as did the sap of various trees. We gathered wild mushrooms and prepared them any way possible, from sauteing, boiling, to baking them, and, for the future, drying and pickling them. Although never developing the taste for mushrooms, I was considered quite an expert in choosing which ones were edible and which were poisonous.

We gathered berries and made soups, compotes, and puddings from them, provided there were other ingredients on hand. My mother, bartering, exchanged her precious Persian carpets, the paintings of such famous Russian artists as Aivasovsky, Repin and Shishkin, all originals, for a sack of potatoes or a sack of flour. Our main interest were staying alive.

What did I think? What did I feel? I thought of poetry, of books, the stories I read, or those that were read to me, the goats I played with in the outskirts of Berlin. I thought of the young man, whom I worshipped, who when visiting us with his fiancee recited his poetry to me and took me for walks in the woods, carving our initials on a tree. I thought of the dark secret my cousin Olga and I shared of the knowledge that some of our family members and close friends, including my hero, the poet, were arrested and put into a place called "Sachsenhausen". These facts were kept from us, lest we divulge that information to our neighbors and playmates endangering us all. I thought of my father who was far away, of my godfather who came to us, sometimes in the middle of the night, conversing in subdued tones with my family. I thought of the nightmares and the fears.

What did I feel? I felt fear, panic, confusion and total futility. My uncle Seraphim, before his arrest, would predict that soon the war would be over and everything would go back to normal. How could it? We had lost our spiritual innocence, we had lost almost every material thing we had, the only things left were hope and faith.

How can I explain to my son and others, the emotions we felt, when we heard the German broadcasts of how their army was advancing into Russia, how they treated traitors and deserter, giving graphic details of their executions, how we listened to BBC at night, covering ourselves and the radio with a blanket, so that our landlady would not hear us and report us to the Gestapo. When walking in the woods, I stumbled upon a concentration camp, with a large brick chimney reaching up to the sky, surrounded by barbed wire and furious dogs, barking, foaming at their mouths. How can I explain my thoughts and my feelings, no one would explain to me what I had seen.

When years before, in Berlin, I saw windows being smashed, screaming people being dragged by their hair into vans, my mother covering my eyes and spiriting me away, what did I feel, what did I think? When we were near starvation and I would not eat the flesh of the goats that had been my friends, I was told horror stories about starving children, especially one about a girl who was very weak from hunger, and, when her parents killed her pet pigeon, refused to eat it and died. My relatives, probably, thought that this would make me eat.

What did I think, what did I feel, when the Hitler Youth would come knocking at our door day or night, rattling their tin cans demanding coins for the war effort, when the secret police would burst into our home examining all books and not finding the forbidden works of Heinrich Heine ("The Lorelei"), which were hidden underneath Hitler's "Mein Kampf" in my mother's hope chest. What did I think when handsome men and women, their heads hung low, walked in the street with a yellow star proclaiming "Jude" (Jew) on their coat? When others had the emblem "OST" on their clothes identifying them as force labor from the East. And, finally, what did I think and how did I feel, when my beloved books, that my mother so lovingly collected, were thrown into a bonfire by our landlady?

True, there were times, when I did not think about anything, when my fears were subdued, those were the times when my baby cousin Nikki was born, when I appointed myself as his guardian, his protector. The times when gathering flowers, covered with the morning dew, I would weave them into wreaths and garlands to decorate my cousin Olga's chair and breakfast table to celebrate her birthday. I would join into the songs, albeit sad ones, that my aunt Anna sang, I would relish and never forget the time my cousin Tania invited me for dinner and served my favorite meal with food she got at the black market.

Neither will I forget the times, when my family had a poetry contest, I still remember the words to the poem Olga's mother wrote. I remember my uncle Yuri taking me for rides in the woods and on the beach on his bicycle, pedaling like crazy, while I hung on for dear life. I remember the vegetable garden my grandfather planted and the stories, poems and songs he used to recite.

But

how do I tell my son all this? He would not understand ..."

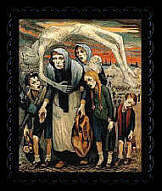

Holocaust

Art:

David Olére, Gideon, Josef Elgurt, Josef Nassy